threatened

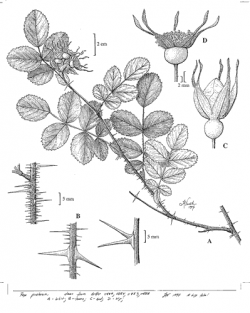

Line drawing showing A) habit; B) sections of stem showing prickles; C) flower bud; and D) mature hip (drawn from specimens from S. F. B. Morse Botanical Preserve, Del Monte Forest). Linda Vorobik © 1997. Visit her website at: http://www.vorobikbotanicalart.com

Pine rose habitat in open understory of native Monterey pine forest, S.F.B. Morse Botanical Preserve, Del Monte Forest. Photo © Barbara Ertter.

Photo taken at S. F. B. Morse Botanical Preserve, Del Monte Forest, Pebble Beach in mixed Monterey pine, oak, and redwood forest by Rod M. Yeager, MD © 2008.

Photo taken at S. F. B. Morse Botanical Preserve, Del Monte Forest, Pebble Beach in mixed Monterey pine, oak, and redwood forest by Rod M. Yeager, MD © 2008.

Photo taken at S. F. B. Morse Botanical Preserve, Del Monte Forest, Pebble Beach in mixed Monterey pine, oak, and redwood forest by Rod M. Yeager, MD © 2008.

This fact sheet was prepared by Dylan M. Neubauer under award NA04N0S4200074 from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), U.S. Department of Commerce (DOC). The statements, findings, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the NOAA or the DOC.

© Copyright 2006, Elkhorn Slough Coastal Training Program

Last updated: Nov 16, 2017 17:32

Common Names - pine rose

Family - Rosaceae (Rose Family)

State Status - none

Federal Status - none

Habitat

Seasonally moist areas in openings in native Monterey pine forest or woodland, occasionally in maritime chaparral; generally < 300 m.

Key Characteristics

Small shrub, generally < 10 dm tall, forming open colonies and not thicket-forming; stem with many prickles, 3–10 mm long, generally not paired, both slender and ± thickened at the base; leaf axis glabrous or finely hairy, glandular; leaflets 5–7, glabrous to hairy, terminal leaflet 10–30 mm, generally ± elliptic, widest near middle, tip ± obtuse, margins ± single- or double-toothed, ± glandular; inflorescence generally 1–5-flowered; pedicels generally 10–30 mm, glabrous, glandular or not; hypanthium generally ± 4 mm wide at flower, glabrous, glandless, neck ± 3 mm wide; sepals generally ± glandular, entire, tip generally ± = body, entire or toothed; petals ± 15–20 mm, pink; pistils ± 10–20; fruit ± 12 mm wide, spheric; sepals in fruit persistent, ± erect. (Ertter 2001, 2014).

Rosa gymnocarpa, with sepals deciduous in fruit, generally reaches 5–20 dm. It has stems with prickles few to many; leaflets generally (5)7–9, glabrous, with glandular teeth; pedicel generally stalked-glandular; the glabrous and glandless hypanthium is 1.5–2 mm wide at flower; and pistils number 5–10. It generally grows in shade to semi-shade in forest or scrub.

Rosa spithamea, with sepals persistent in fruit, is generally < 5 dm tall and has prickles few to many and prominent, stalked glands on the hypanthium at flower. It grows in open forest and chaparral, and is often a fire-follower. The “nearest known populations of R. spithamea” are “well removed from known populations of R. pinetorum, however, hybrids of R. gymnocarpa and R. spithamea can key to R. pinetorum (Lewis et al. 2014; Ertter 2015).

Rosa californica, which grows with R. pinetorum on the Monterey Peninsula, is thicket-forming, reaches 8–25 dm, and has compressed, generally curved prickles with thick bases. It generally favors moist areas, and is often found along streams (Ertter 2015).

Flowering Period

May-June

Reference Population

S. F. B. Morse Botanical Reserve (Monterey County)

Global Distribution

Restricted to the central California coast. Known from coastal terraces on the Monterey Peninsula to Carmel Highlands (Monterey County), the mouth of Waddell Creek at Big Basin Redwoods State Park (Santa Cruz County), and possibly Cambria (San Luis Obispo County) (Lewis et al. 2014).

Taxonomic History

Due to their “extensive phenotypic plasticity, rampant hybridization, and polyloidy” (Ertter and Lewis 2008), members of the genus Rosa are notoriously difficult to classify and, as a result, have a “complex nomenclatural history” (Ertter 2001; Bruneau et al. 2007). Ertter (2001) notes that, in California alone, about “60 species names have been proposed and applied.” Recent DNA analysis (Bruneau et al. 2007) has only confirmed this difficulty, revealing only a “paucity of differentiation between rose species at the molecular level.” Indeed, it has been said that applying the “classic biological species concept to Rosa” may yield only a few species worldwide! (B. Ertter, pers. comm.).

Historically, the epithet Rosa pinetorum has been applied to “dwarf roses throughout the Coast Ranges and Sierra Nevada of California that “lacked the conspicuous stipitate hypanthial glands that characterize R. spithamea” (Lewis et al. 2014). In the Coast Ranges, however, stipitate glands may or may not be present in R. spithamea, probably as a result of hybridization—a fact mentioned in the 2014 Flora of North America treatment (Lewis et al.). Current treatments (Lewis et al. 2014; Ertter 2016) only “tentatively” retain R. pinetorum “as a distinct species” and restrict its range to the Central Coast in general and the Monterey Peninsula in particular—citing the presence of other highly “localized endemic species” in this area and the significant distance from known populations of R. spithamea. The authors also note that plants “assigned to this reduced circumscription clustered with R. gymnocarpa in a molecular phylogenetic analysis” (see Bruneau et al. 2007). More detailed research is needed to determine whether this clustering indicates a “close relationship” between these two taxa or whether it is due to introgression (Lewis et al. 2014).

Biology and Ecology

As Barbara Ertter notes on her website on native California roses, “the handful of populations currently identified as Rosa pinetorum exhibit greater morphological variation than would be logically expected in a single localized species” (2001). One scenario that might explain this variability invokes the ideas of ecologist Edgar Anderson (1948, 1949), who investigated the long-observed connection between habitat disturbance and hybridization. Perhaps the ancestral R. pinetorum genome was restricted to the Monterey Peninsula, along with Monterey cypress (Hesperocyparis macrocarpa) and Gowen cypress (Hesperocyparis goveniana)—both of which are now on the verge of extinction there. Habitat alteration (or “habitat hybridization”) from human activities may then have brought R. pinetorum in greater contact with other native rose species with which hybridization may have occurred—and which may have resulted in “genetic swamping” of the R. pinetorum genome. More genetic studies are necessary to tease out these relationships (D. W. Taylor, pers. comm.).

Conservation

The type locality of Rosa pinetorum at Point Pinos in Pacific Grove on the Monterey Peninsula was based on collections made from 1903–1931. It has been extirpated for many decades due to development in this area.

Occurrences at Veterans Memorial Park, the S. F. B. Morse Preserve, and Pebble Beach on the Peninsula are presumed extant, and conservation and proper management of these “core” populations are crucial for the retention of the R. pinetorum genome.

The current status of plants at Point Lobos State Natural Reserve is unknown. An occurrence along Gibson Creek east of Point Lobos is based on a 1936 specimen and is in an area that has been developed. An occurrence on Lobos Ridge was observed in 2003 and is threatened by development.

Plants that key to this species have been observed in Carmel Valley at the Santa Lucia Preserve and at Garland Ranch Regional Park, though these have not been officially documented.

The one Santa Cruz County occurrence at the mouth of Waddell Creek in Big Basin Redwoods State Park in the Monterey pine forest was last documented in 1932. A Felton specimen/occurrence has since been determined to be R. gymnocarpa.

Other populations outside the expected habitat of Monterey pine forest are based on specimens that key to R. pinetorum. Some of these may be hybrids between R. gymnocarpa and R. spithamea. Until further genetic/field work is conducted, however, these populations should be managed as R. pinetorum.

References

Anderson, E. 1948. Hybridization of the habitat. Evolution 2(1):1–9. http://doi.org/10.2307/2405610 [accessed 2 January 2016].

Anderson, E. 1949. Introgressive hybridization. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, NY, Chapman & Hall, Ltd., London.

Bruneau, A., J. R. Starr, and S. Joly. 2007. Phylogenetic relationships in the Genus Rosa: new evidence from chloroplast DNA sequences and an appraisal of current knowledge. Systematic Botany 32(2):366–378.

CNPS, Rare Plant Program. 2014. Rosa pinetorum, in Inventory of Rare and Endangered Plants (online edition, v8-02). California Native Plant Society, Sacramento, CA. http://www.rareplants.cnps.org/detail/1356.html [accessed 19 December 2015].

Ertter, B. 2001. Native California roses: an on-line monograph of native Rosa in California prepared for The Jepson manual: higher plants of California (1993). http://ucjeps.berkeley.edu/ina/roses/rose_history.html [accessed 19 December 2015].

Ertter, B. 2015. Rosa pinetorum, Revision 2, in Jepson Flora Project (eds.) Jepson eFlora, http://ucjeps.berkeley.edu/cgi-bin/get_IJM.pl?tid=41684 [accessed 23 December 2015].

Ertter, B. and W. H. Lewis. 2008. New Rosa (Rosaceae) in California and Oregon. Madroño 55(2):170–177.

Lewis, W. H., B. Ertter, and A. Bruneau. 2014. Rosa. In: Flora of North America Editorial Committee, eds. 1993+. Flora of North America North of Mexico. 19+ vols. New York and Oxford. Vol. 9. http://www.efloras.org/florataxon.aspx?flora_id=1&taxon_id=250100422 [accessed 19 December 2015].

Taylor, D. W. Personal communication [December 2015].

Vorobik, L. 1997. Line drawing of R. pinetorum. Visit her website at: http://www.vorobikbotanicalart.com

Reviewers

Nikki Nedeff, Biological Consultant (March 2016)