endangered

Photo taken at the Bonny Doon Ecological Reserve © 2007 Dylan Neubauer.

Photo taken at the Olympia Quarry with Ben Lomond spineflower (Chorizanthe pungens var. pungens) in background and with Chalcedon Checkerspot (Euphydryas chalcedona) visiting the flowers © 2011 Dylan Neubauer.

Photo taken at the Olympia Quarry © Dean W. Taylor

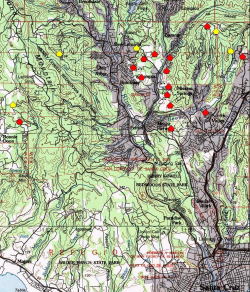

A red polygon indicates an extant occurrence; yellow indicates the occurrence has been extirpated.

This fact sheet was prepared by Dylan M. Neubauer under award NA04N0S4200074 from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), U.S. Department of Commerce (DOC). The statements, findings, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the NOAA or the DOC.

© Copyright 2006, Elkhorn Slough Coastal Training Program

Last updated: Jun 19, 2007 17:40

Common Names - Ben Lomond wallflower

Family - Brassicaceae (Mustard Family)

State Status - state endangered

(September 1984)

Federal Status - federal endangered

(June 1992)

Habitat

Openings in sandhills chaparral or in sand parkland with occasional Pacific ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa var. ponderosa) on soils of the Zayante series in inland areas of uplifted Miocene marine sediments and sandstones of the Santa Margarita Formation. These areas are termed variously the Zayante, Ben Lomond, or Santa Cruz sandhills (McGraw 2004).

Key Characteristics

Biennial or short-lived perennial herb from caudex, generally to 8 dm tall, proximal stems not woody; leaves in basal rosette, purplish green, thread-like to narrowly linear, to 3 mm wide, finely toothed, somewhat rolled under, appearing cylindric, trichomes generally bifurcate; inflorescence terminal (or axillary if browsed), racemose, elongated; petals 15–20 mm long, brilliant yellow or orange-yellow, faintly scented; pedicel spreading to ascending, 5-14 mm; fruit to 12 cm, ± flat parallel to septum, ± constricted between seeds, midvein prominent (Al-Shehbaz 2013).

Flowering Period

March to June

Reference Population

Bonny Doon Ecological Reserve, Quail Hollow Ranch State Park (Santa Cruz County).

Global Distribution

Endemic to the southern Santa Cruz Mountains of California

Conservation

A recent captive breeding study (Melen 2014) found that self-pollination resulted in significantly fewer viable seeds than outcrossed pollinations, meaning that self-incompatibility is likely (as is the case with most members of the Mustard Family). The study emphasized that promotion of pollinators and their habitat may prove essential in conserving this species. Another recent study assessing genetic diversity in historically isolated and now fragmented populations found that more genetic diversity exists within rather than between populations (Herman et al. 2014), implying that the origin of propagules may not prove critical for reintroduction.

It is likely that populations were once more widely scattered throughout the sandhills before habitat fragmentation and fire-suppression (USFWS 2008). Most habitat has been severely impacted by sand mining and residential development. Fire-suppression has caused habitat conversion with the invasion of woody species, non-native grasses, and build-up of leaf litter in open areas favored by Ben Lomond wallflower. Overall, these effects, along with large- and small-mammal herbivory, negatively impact size and fecundity (Brunette 1997, McGraw 2004).

Census information shows a declining trend with a 40% reduction from the highest recorded numbers (USFWS 2008). USFWS (2008) reported that of the 20 populations examined, only two were considered stable with extensive management including planting, while three were decreasing and three others extirpated.

The Bonny Doon Ecological Reserve occurrence has declined dramatically, from ca. 1000 plants in 1986 to a few dozen or less annually in recent years, with few seedlings (Parker et al. 2011). Plants in this population appear to have reduced reproductive success, possibly due to self-incompatibility resulting from high levels of self-pollination (Parker et al. 2011, Melen 2014). Brunette (1997) found no detectable soil seed bank in this population. Herbivory by deer and other small mammals is also a factor (Brunette 1997, McGraw 2004b).

References

Al-Shehbaz, I. A. 2013. Erysimum, in Jepson Flora Project (eds.). Jepson eFlora, http://ucjeps.berkeley.edu/cgi-bin/get_IJM.pl?tid=25143 [accessed 10 February 2015].

Brunette, A. 1997. The seed bank and population structure of two populations of the rare and endangered plant Erysimum teretifolium (Brassicaceae). Senior Thesis, Environmental Studies, University of California, Santa Cruz.

CNPS, Rare Plant Program. 2010. Erysimum teretifolium, in Inventory of Rare and Endangered Plants (online edition, v8-02). California Native Plant Society, Sacramento, CA. http://www.rareplants.cnps.org/detail/796.html [accessed 10 February 2015].

Herman, J. A., K. DeJan, J. B. Whittall. 2014. Assessing genetic diversity in the rare sandhill endemic Erysimum teretifolium using microsatellites and next-generation sequencing. Santa Clara University.

Marangio, M. and R. Morgan. 1987. The endangered sandhills plant communities of Santa Cruz County. Pp. 267-271, in T. S. Elias, ed., Conservation and Management of Rare and Endangered Plants. California Native Plant Society Press, Sacramento, CA.

McGraw, J. M. 2004. The sandhills conservation and maangement plan: a strategy for preserving native biodiversity in the Santa Cruz sandhills. Prepared for The Land Trust of Santa Cruz County. http://www.santacruzsandhills.com/articles/Sandhills%20Conservation%20and%20Management%20Plan%20June%202004.pdf [accessed 10 February 2015].

Melen, M. K. 2014. Sandhills endemic Erysimum teretifolium (Brassicaceae) benefits from outcrossing. Masters Thesis, San Jose State University. http://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=7978&context=etd_theses [accessed 9 February 2015].

Parker, I. M., A. Weitz, and K. Webster. 2011. Reproductive bottlenecks in Ben Lomond wallflower (Erysimum teretifolium). University of California, Santa Cruz.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2008. Ben Lomond wallflower (Erysimum teretifolium) 5 year-review: summary and evaluation. Ventura Office, Ventura, CA. http://ecos.fws.gov/docs/five_year_review/doc1934.pdf [accessed 10 February 2015].