endangered

Illustration from Abrams (1944).

Photo taken at the Bonny Doon Ecological Reserve © 2007 Dylan Neubauer.

Photo © 2007 Dylan Neubauer.

Photo of a single plant © 2007 Dylan Neubauer.

Photo taken at the Bonny Doon Ecological Reserve © 2007 Dylan Neubauer.

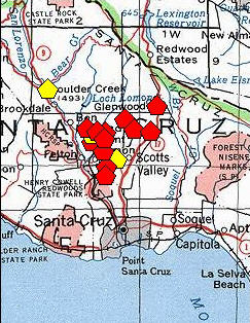

A red polygon indicates an extant occurrence; yellow indicates the occurrence has been extirpated.

This fact sheet was prepared by Dylan M. Neubauer under award NA04N0S4200074 from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), U.S. Department of Commerce (DOC). The statements, findings, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the NOAA or the DOC.

© Copyright 2006, Elkhorn Slough Coastal Training Program

Last updated: Mar 26, 2016 18:58

Common Names - Ben Lomond spineflower

Family - Polygonaceae (Buckwheat Family)

State Status - none

Federal Status - federal endangered

(February 1994)

Habitat

Openings in sandhill chaparral, or scattered in the understory of Pacific ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa var. ponderosa) forests in areas of Miocene inland marine sand deposits (Zayante series) in the southern Santa Cruz Mountains. These areas are termed variously the Zayante, Ben Lomond, or Santa Cruz sandhills (Marangio and Morgan 1987).

Key Characteristics

Annual herb, ascending to erect, 0.5–2.5 dm tall, hairy; leaves in basal rosette and at lowest few nodes, oblanceolate, blades .5–5 cm; inflorescence dense, cymose; bracts 2, awned, awns 0.5-1.2 mm; involucre 3-angled, 6-ribbed, tube 2–3 mm long, ± swollen, transversely ridged, teeth 6, 0.5–1 mm, margins dark pink to purple, awns 1–3 mm, hooked; flower 1, 2–3.5 mm, hairy, perianth 2-colored, tube white, lobes white to rose, jagged; stamens 9 (Reveal and Rosatti 2013). Based on growth habit and involucre-teeth margin color, not readily confused with Monterey spineflower (C. pungens var. pungens), but more easily confused with Scotts Valley spineflower (C. robusta var. hartwegii) (w/ involucre tube 2.5–3.5 mm), though the latter has a highly restricted distribution in Scotts Valley (Santa Cruz County).

Flowering Period

April to July

Reference Population

Bonny Doon Ecological Reserve (Santa Cruz County).

Global Distribution

Endemic to the Santa Cruz Mountains of California (Santa Cruz County).

Conservation

The Ben Lomond spineflower was given a Recovery Priority of 9 in the latest 5-year Review by USFWS (2012), meaning that it is considered to face a moderate degree of threat while having a high potential for recovery.

A 2009 genetic study of the Pungentes subsection of Chorizanthe (Brinegar and Baron) suggests that there is a closer phylogenetic relationship between the Ben Lomond spineflower and the Scotts Valley spineflower (C. robusta var. hartwegii)--both of which grow inland--than between the Ben Lomond spineflower and the coastal Monterey spineflower (C. robusta var. robusta). The current Jepson Manual/eFlora treatment (Reveal 2013) does not reflect this information.

According to a 1998 study (McGraw and Levin), plants are least successful (in growth, survivorship, and reproduction) when grown on their native, low-nutrient soil suggesting that the distribution of Ben Lomon spineflower is not limited by soil type. However, intolerance to shade could be a major cause of the spineflower's restriction to open, sandy, often disturbed areas such as trail edges and gopher mounds (McGraw 2004). As shrubs and non-native species invade open areas due to lack of fire, those areas then become unsuitable for Ben Lomond spineflower (Kluse and Doak 1999). Competition with the non-native grass rat-tail fescue (Festuca myuros) has been shown to significantly inhibit growth and reproductive success of Ben Lomond spineflower where they co-occur (Pollock 1995). Soil seed storage is not well understood, making it probable that small occurrences in residential areas will decline over time. Some plants with pale pink perianths are intermediate to C. p. var. pungens.

References

Abrams, L. 1944. Illustrated Flora of the Pacific States, Vol. 2. Stanford University Press, Palo Alto, CA.

Brinegar, C. and S. Baron. 2009. Molecular phylogeny of the Pungentes subsection of Chorizanthe (Polyognaceae: Eriogonoideae) with emphasis on the phylogeography of the C. pungens–C. robusta complex. Madroño 56(3):168–183.

CNPS, Rare Plant Program. 2015. Chorizanthe pungens var. hartwegiana in Inventory of Rare and Endangered Plants (online edition, v8-02). California Native Plant Society, Sacramento, CA. http://www.rareplants.cnps.org/detail/1626.html [accessed 2 February 2015].

Kluse, J. and D. F. Doak. 1999. Demographic performance of a rare California endemic, Chorizanthe pungens var. hartwegiana (Polygonaceae). American Midland Naturalist 142(2):244–256.

Marangio, M. and R. Morgan. 1987. The endangered sandhills plant communities of Santa Cruz County. In Conservation and Management of Rare and Endangered Plants: Proceedings From a Conference of the California Native Plant Society, T. S. Elias, editor. California Native Plant Society Press, Sacramento, CA.

McGraw, J. M. 2004. Sandhills Conservation and Management Plan. Prepared for The Land Trust of Santa Cruz County. http://www.santacruzsandhills.com/articles/Sandhills%20Conservation%20and%20Management%20Plan%20June%202004.pdf [accessed 2 February 2015].

McGraw, J. M. and A. L. Levin. 1998. The roles of soil type and shade intolerance in limiting the distribution of the edaphic endemic Chorizanthe pungens var. hartwegiana (Polygonaceae). Madroño 45(2):119-127.

Pollock, J. F. 1995. A study of fire and competition effects on Chorizanthe pungens var. hartwegiana in the sandhills of Santa Cruz County, California, using a stage-based matrix model and Lotka Volterra 65 competition equations. Senior thesis, Environmental Studies, University of California Santa Cruz.

Reveal J. L. and T. J. Rosatti. 2013. Chorizanthe, in Jepson Flora Project (eds.). Jepson eFlora, http://ucjeps.berkeley.edu/eflora/eflora_display.php?tid=56500 [accessed 2 February 2015].

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2012. Chorizanthe pungens var. hartwegiana (Ben Lomond spineflower) 5-year review: summary and evaluation. Ventura Fish and Wildlife Office, Ventura, CA. http://ecos.fws.gov/docs/five_year_review/doc3973.pdf [accessed 2 February 2015].