endangered

Illustration from Ferris (1960).

Photo from the S.F.B. Morse Botanical Reserve © Dean W. Taylor.

Photo taken at Ford Ord National Monument © 1998 Bruce Delgado.

Photo taken at Fort Ord © 2007 Dylan Neubauer.

Photo taken at Fort Ord © 2007 Dylan Neubauer.

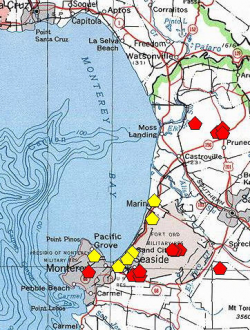

A red polygon indicates an extant occurrence; yellow indicates the occurrence has been extirpated.

This fact sheet was prepared by Grey F. Hayes and Dean W. Taylor under award NA04N0S4200074 from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), U.S. Department of Commerce (DOC). The statements, findings, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the NOAA or the DOC.

© Copyright 2006, Elkhorn Slough Coastal Training Program

Last updated: Sep 3, 2007 09:09

Common Names - Eastwood's goldenbush

Family - Asteraceae (Sunflower Family)

State Status - none

Federal Status - none

Habitat

Sandy, inland, pre-Flandrian sand deposits (Arnold series) overtopping leached Aromas Sands Formation parent material; mesas and hillsides adjacent to maritime chaparral and in gaps between shrubs, along edges of coast live-oak (Quercus agrifolia var. agrifolia) woodland, and in edges between chaparral and coastal sage scrub; under canopy and in association with Gowen cypress (Hesperocyparis goveniana); disturbed edges of graded roadways; < 100 m.

Key Characteristics

Subshrubs, top rounded, <= 15 dm tall, stems erect to ascending, green when young, fastigiately branched, densely leafy, glabrous to sparsely puberulent, resinous, branches ascending; leaf blades filiform, reflexed with age, gland-dotted in pits, axillary clusters of 2–10 shorter leaves generally present; heads generally radiate, 1-few in cyme-like clusters, bracts leaf-like, phyllaries 22–26 (16–24 in E. ericoides), outermost not leafy (outermost leafy in E. ericoides); ray flowers 4–6 (2–6 in E. ericoides), disk flowers 18–25 (5–14 in E. ericoides); cypselae generally silky to densely hairy (glabrous to silvery hairy, more densely distally in E. ericoides) (Urbatsch 2013).

Flowering Period

July to October

Global Distribution

Fort Ord National Monument, Toro County Park, Manzanita County Park, S.F.B. Morse Botanical Reserve (Monterey County).

Conservation

Thousands of acres of protected habitat are present on the Fort Ord National Monument. Twenty years of weed abatement on the Monument has clearly benefitted this and other rare species. Several locations of older herbarium collections near Monterey are presumed extirpated. One large occurrence near the Monterey Airport was nearly eliminated by development in the late 1980s. Plant likes to colonize disturbed areas, so often gets sprayed with herbicide inadvertently. This has occurred in both Manzanita County Park and the S.F.B. Morse Botanical Reserve.

Other threats include competition from non-natives and fire suppression. It is thought the species is a facultative, rather than an obligate, resprouter—i.e., it does not require fire to sprout. After a burn, plants resprout vigorously, though smaller and larger-sized plants do not resprout as well as average-sized plants. In addition, the fact that the species is not an obligate seeder—75% of seeds are empty—leads to a very limited range of dispersal. Low-intensity burning has been recommended to maintain populations. Plants that have resprouted once following a fire have a hard time doing it a second time, but immature plants are more resilient. Therefore, low-intensity burning will favor the younger plants, thus altering the demographics of the population. Despite this, burning should help in the long run, since it also decreases the threat of competition from non-natives. Active restoration that inhibits the establishment of weeds post burning is also recommended.

When not in bloom, E. fasciculata is relatively difficult to separate from the more common and widespread E. ericoides. The two taxa are closely related (Roberts and Urbtasch 2003) but often ecologically separated: E. ericoides occurs on mobile to stable but young sand deposits and E. fasciculata occurs on older, interior sand deposits.

References

CNPS, Rare Plant Program. 2011. Ericameria fasciculata, in Inventory of Rare and Endangered Plants (online edition, v8-02). California Native Plant Society, Sacramento, CA. http://www.rareplants.cnps.org/detail/606.html [accessed 6 February 2015].

Ferris, R. S. 1960. Illustrated Flora of the Pacific States, Vol. 4. Stanford University Press, Palo Alto, CA.

Griffin, J. R. 1978. Maritime chaparral and endemic shrubs of the Monterey Bay region, California. Madroño 25(2):65–81.

Roberts, R. P. and L. E. Urbtasch. 2003. Molecular phylogeny of Ericameria (Asteraceae, Astereae) based on nuclear ribosomal 3 ETS and ITS sequence data. Taxon 52(2):233–245.

Urbatsch, L. E. 2013. Ericameria fasciculata, in Jepson Flora Project (eds.). Jepson eFlora, http://ucjeps.berkeley.edu/eflora/eflora_display.php?tid=2593 [accessed 6 February 2015].

Van Dyke, E. and K. Holl. 2003. Mapping the distribution of maritime chaparral species in the Monterey Bay Area. Prepared for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Ventura Fish and Wildlife Office, Ventura, CA. http://www.elkhornsloughctp.org/uploads/files/1123621594Van%20dyke%20holl%20dist%20of%20mar%20chap.pdf [accessed 6 February 2015].

Reviewers

John Detka, Eric Van Dyke (August 2007); Bruce Delgado (August 2007, June 2015).